Hello from Riyadh - welcome to Growing Meta, and Eid Mubarak! 🎆

I created this newsletter to share the most insightful bites of scholarly conclusions and discoveries that augment our understanding of knowledge & complexities. This newsletter will slowly converge into a mountain range of meta — what are the best lenses that view all other lenses?

This week, I read a fantastic (and incredibly well-written) essay on Christopher Alexander’s works.

“A Search for Beauty/A Struggle with Complexity: Christopher Alexander” by Richard P. Gabriel, and Jenny Quillien.

It is so dense with analysis and is worth a read if you are interested in design and complexity.

Here are some highlights (all quotes are excerpts from the essay):

Beauty. Christopher Alexander’s prolific journey in building, writing, and teaching was fueled by a relentless search for Beauty and its meaning.

Christopher Alexander, an architect and a design theorist who is currently teaching at UC Berkeley, has embraced complexity as a necessity to consider when designing towards beauty. His works influenced many fields: urban design, software design, sociology, amongst others.

What Alexander didn’t agree with:

“oversimplification,

deliberately bulldozing context,

misunderstanding the relationships of part and whole,

ignoring the required role of time in the shaping of shapes, and

ultimately dismissing, like Esau, our birthright of Value in favor of a lentil pottage of mere Fact.” (or, in other words: beauty is subjective)

Here is a summary of some of Alexander’s major works:

A City is not a Tree (1965)

This landmark essay (now a book) is a reference for urban design.

Alexander argues that designed towns should not be designed like trees (Figure 1b). Cities should be designed like a complex network, like “semi-lattices” (Figure 1a). A city consists of many things: people, points-of-interests, roads, utilities, and many others. These elements have interdependent relationships with each other, just like any complex system. Natural city designs must be based on these relationships.

Alexander gives an example on semi-lattice design:

“Here is an example. In Berkeley, at the corner of and Euclid, there is a drug store, and outside the drug store a traffic light. In the entrance to the drug store there is a newsrack where the day's papers are displayed. When the light is red, people who are waiting to cross the street stand idly by the light; and since they have nothing to do, they look at the papers displayed on the newsrack which they can see from where they stand. Some of them just read the headlines, others actually buy a paper while they wait.

This effect makes the newsrack and the traffic light interdependent; the newsrack, the newspapers on it, the money going from people's pockets to the dime slot, the people who stop at the light and read papers, traffic light, the electric impulses which make the lights change, the sidewalk which the stand on form a system - they all work together.” — Alexander, A City is Not a Tree

The problem of building semi-lattice models is in its size. You can’t wrap your head around the complexity easily.

To get an idea of the difference in complexity between tree and semi-lattice models, consider that a tree model based on 20 elements can maximally contain 19 subsets of the 20 elements … while a semi-lattice based on the same 20 elements makes room for over 1,000,000 subsets … If it were 50 instead of 20, the number would start ‘one quadrillion . . . .’

Slides by Sadi Murshed Bhuiyan

A Pattern Language

Here is an interesting fact:

The book, A Pattern Language [13], was the outcome of a Request for Proposal (RFP) posted by the American Government. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) wanted to know if there was a relationship between the built environment and human well-being. They would pay for research. Alexander and colleagues responded to this RFP in a curious way: not only did they not know the answer, they admitted that they had no idea about how to find out. That said, it was an interesting question and they were willing to give it a try. They got the job.

The book, written by Alexander and his team, describe 253 different patterns that can be used in design.

To summarize the essentials: a pattern language is a set of abstract instructions, called “patterns,” which address recurring problems and tell people what they need to do in order to resolve those problems, along with a set of sequences—the order in which to consider the patterns.

Each implementation will be different and finely adjusted to its context.

15 Principles of Wholeness (what makes a design alive) as listed in the book - Slide by Sadi Murshed Bhuiyan

The Nature of Order (4 Volumes, 2002-2005)

Alexander wasn’t happy that designers were using patterns, but not speaking its language.

It is at this stage that Alexander seemed to come upon one of the most interesting parts of his thinking about organized complexity: the paradoxical interplay between symmetry and asymmetry, or between simplicity and complexity.

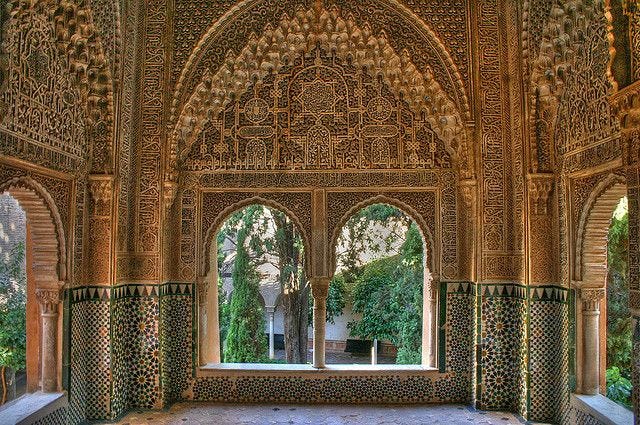

He dissects Alhambra palace in Granada. He notes that there is balance between asymmetry and symmetry. Its architects used asymmetry to integrate with nature (being on a hilltop, it was difficult to stay symmetrical), and used symmetry where they could.

“Everything in nature is symmetrical unless there is a reason for it not to be . . . . Within the living cases, we know there is always a balance of symmetry and asymmetry. But we do not know a way to formulate this balance . . . . For the moment, we must just declare [it] an enigma.” {Nature of Order Book Two}.

Alhambra Palace - Concentrated symmetries in its interior (image Source), and major asymmetries in the way it sits on the hill (image Source).

“We define organic order as the kind of order that is achieved when there is a perfect balance between the needs of the parts, and the needs of the whole.” - Christopher Alexander

There is so much on Alexander’s works that is not covered here. But I move to a more recent contribution by Bin Jiang:

Alexandrian Beauty and Computation

In a 2015 paper, Wholeness as a Hierarchical Graph to Capture the Nature of Space, Bin Jiang creates a way to calculate the beauty of centers that Alexander defined.

This is how he calculates it:

he takes Alexander’s concept of wholeness, refer to the 15 properties above

he constructs a ‘hierarchical graph’, with centers (of spaces) as nodes, and their relationship with each other as edges

he uses PageRank to calculate the wholeness score of a center. PageRank is originally developed and used by Google to rank webpages based on the amount of incoming links.

Source: Backlinko

he uses hierarchical level (ht-index) to calculate wholeness of the whole.

He calculates wholeness/liveliness of Swedish roads (organic) with Manhattan’s (grid-like) and concludes Sweden’s “far more heterogeneous and far larger than the latter.”

He also calculates Alhambra’s wholeness as an extension of Alexander’s work.

Figure source: Jiang, B. A City is a Complex Network. In A City is Not a Tree; Mehaffy, M., Ed.; Sustasis Foundation: Portland, OR, USA, 2015.

I’m considering doing a more thorough coverage of Christopher Alexander and how he influenced

Meta Finds

On Measuring the Beauty in Landscapes:Here is some really interesting research on what makes landscapes beautiful. You may like a certain forest image that another person would not like. They analyze 4 theories that try to explain landscape aesthetics: Habitat theory, Prospect and refuge theory, Affective theory, and Informationprocessing theory.

Their conclusion:

… existing theories based on artistic, bioevolutionary or other properties fail to capture the “richness of human aesthetic response to landscape.” [We] suggest the need for researchers to “broaden their understanding of the multidimensional nature of aesthetic preferences.”

Here are some landscapes close to my hometown.

By photographers Abdulaziz Aldakheel, Ibrahim Sarhan, and Moath Alofi.

I hope you enjoyed it — if you have thoughts on how synthesis and curation can be improved, please reach out!