Hi everyone!

The space of questions is vast.

Yet sometimes, our inherited mindsets limit our capacity for inquiry.

Last week I read two influential papers that illustrate how scientists can get stuck in old paradigms when building knowledge. I composed an illustrated thread that you can read below.

The first essay: Can a biologist fix a radio?—Or, what I learned while studying apoptosis. In this 2002 piece, Lazebnik (a biologist who studies the death of cells) discusses how biologists approach biologist. Early in his career, he “feared that everything in [his] field would be discovered before [he] even had a chance to set up [his] laboratory.” So he decided to consult with a seasoned professor (called Papermaster) who assured Lazebnik that every field he witnessed followed the same pattern:

First stage: A small number of researchers discuss a problem that might seem odd to others (e.g. can cells commit suicide). The researchers are generally friendly and open minded to each other.

Next: An unexpected observation happens (e.g. cells that fail to die can contribute to cancer). This inspires researchers to dig for more unexpected observations using the tools that discovered the initial observation. The field becomes a “Klondike gold rush, with all the characteristic dynamics, mentality, and morals.”

Next: Everyone becomes very motivated to find the “nugget” that will get them published and get them funding. Don’t forget, researchers are human too.

Next: Financial and human resources get poured over this potential “gold mine”. The field expands rapidly. This results in ‘crystal clear’ models that explain everything.

At some stage: These models fall apart. The field hits a wall. But the flood of research still flows in volumes (e.g. 10,000 papers on apoptosis alone in early 2000s). This overwhelms reviewers and authors.

“This stage can be summarized by the paradox that the more facts we learn the less we understand the process we study.”

Even if gold nuggets exist, discovery is not guaranteed. “At this stage, the Chinese saying that it is difficult to find a black cat in a dark room, especially if there is no cat, comes to mind too often.”

If you want to continue meaningful research at this time of widespread desperation, David said, learn how to make good tools and how to keep your mind clear under adverse circumstances.

Read the full commentary for more of his analysis on the way biologists thought.

The second essay builds up on Lazebnik’s rationale and analogy.

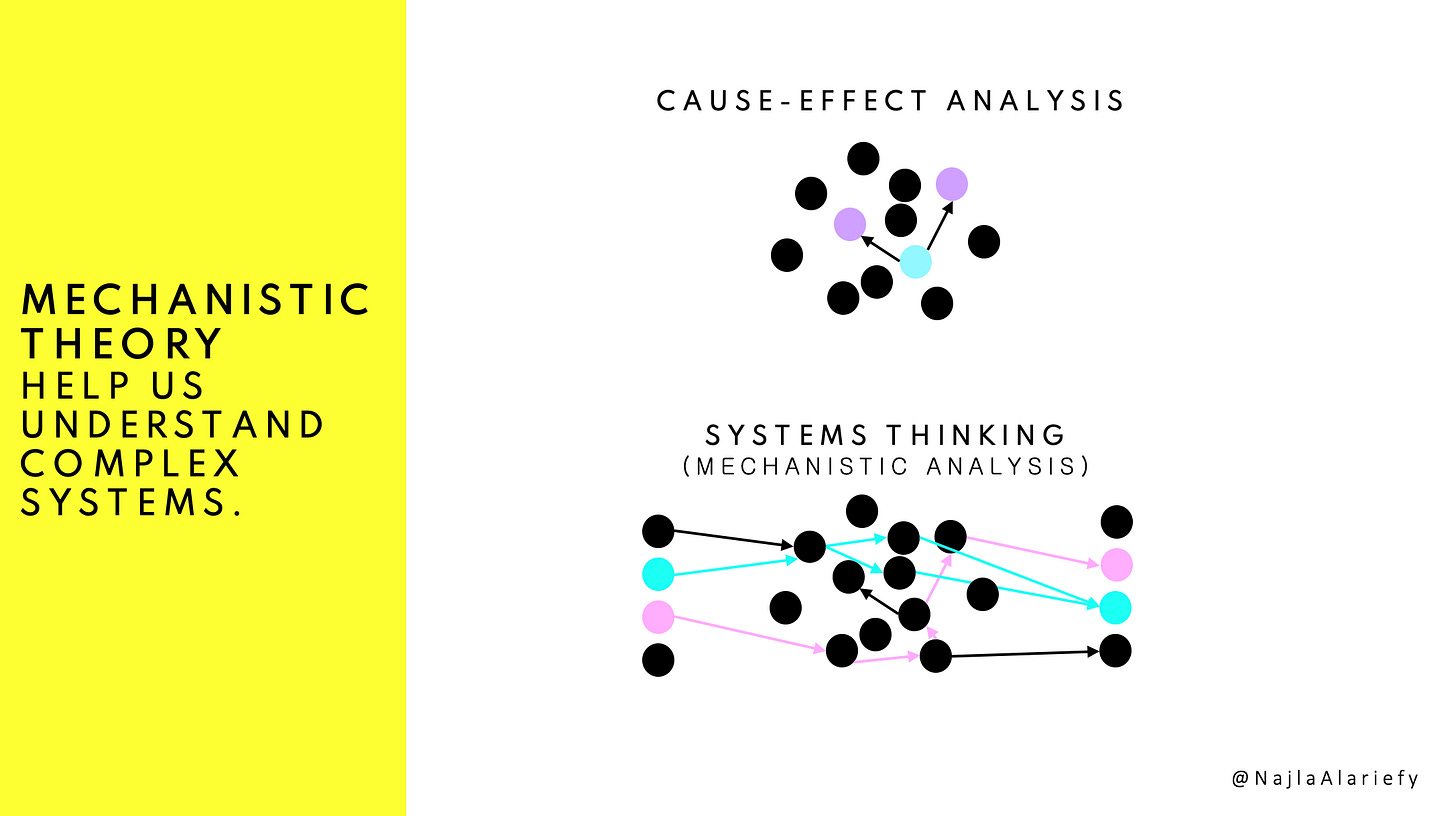

In this second commentary, The tale of the neuroscientists and the computer: why mechanistic theory matters, professor Brown thinks mechanistic theory (understanding why things work the way they do) is crucial to advancing our knowledge about the brain. He also believes we likely need computational power to help us understand the complex mechanisms of the brain. His short essay is worth a read, especially if you’re in a field that does a few types of usual inquiries (like lesion studies, cause/effect mapping etc.)

This was written with love,

Najla

p.s. if you liked this, please share it with someone you think will enjoy reading Growing Meta. I will appreciate it!

Thank you for all the graphics.