Greetings reader,

Back in 2007 I read Stephen King’s post-apocalyptic novel “Cell” about a virus infecting the brains of everyone who had a cellphone at the time of the transmission, leaving a few survivors trying to get through to safe grounds. While I forgot most of the plot, I vividly remember this quote told by one main character who refused to take a risk because it was all based on assumptions: “assuming makes an ass out of u and me”. This quote stuck with me throughout the years as I learned the differences between assumptions and well-grounded inferential statements.

Assumptions arise because we do not have the full picture of anything, or because we have to summarize a set of truths because reality is so complex for us to digest. Assumptions shape a lot of how our world looks like. When a new social media platform is built, it is built on the premise of human responsibility, e.g. that their platform will not be abused by bullies or traffickers. The majority of socio-economic decisions nowadays are built upon assumptions. For example, the assumption that increasing a nation’s GDP is equated with increasing the standards of living, or the coupling of efficiency and financial cost-benefit analyses in driving government policies.

Not only do assumptions drive tech and the economy, but also the pace and direction of scientific discovery. In the field of personalized medicine — which is a breathtaking field of medicine that attempts to identify the genetic underpinnings of each individual disease — it is often assumed that by mapping diseases to our genetic makeup in one large database, we would have the most ideal way in identifying disease risks or in treating a person. Yet this medical approach is far from ideal for several reasons, including that the genetic variations of each disease are not significant enough for predicting risk of diseases, and that the cost of pursuing personalized medicine far exceeds normal medical treatment [2]. So what defines ideal, given limitations in instrumentations and in budgets? The promises that personalized medicine gives (and partially fulfills) has aggregated billions of US dollars in investments with projected growths in demand and in the amount of discoveries [3], regardless, it is humbling to understand the assumptive nature in which scientific discovery is being guided.

On a side note, the debate of personalized medicine vs. traditional medicine reminds me of the debate on micro vs. macro economics. A debate of constraints and appetite for precision.

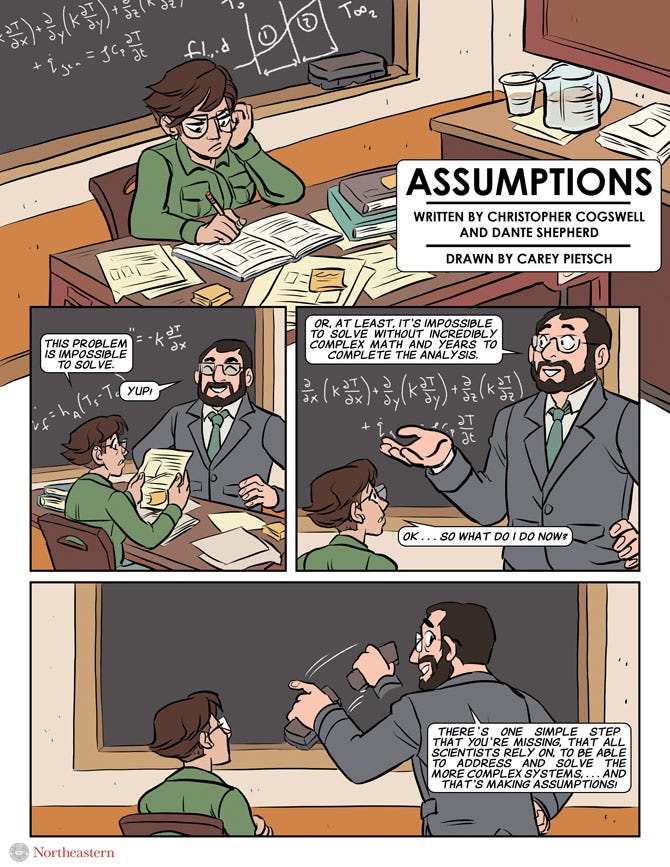

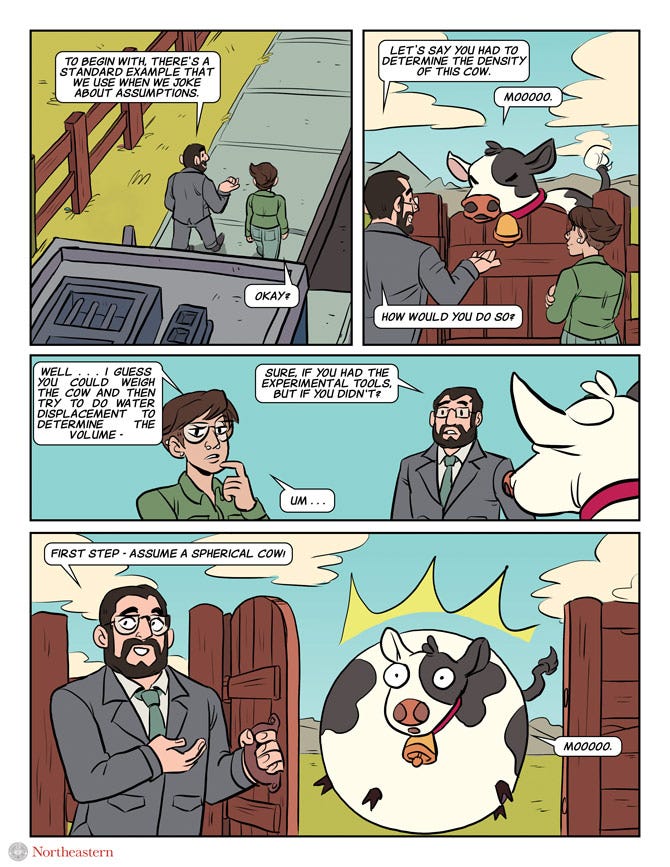

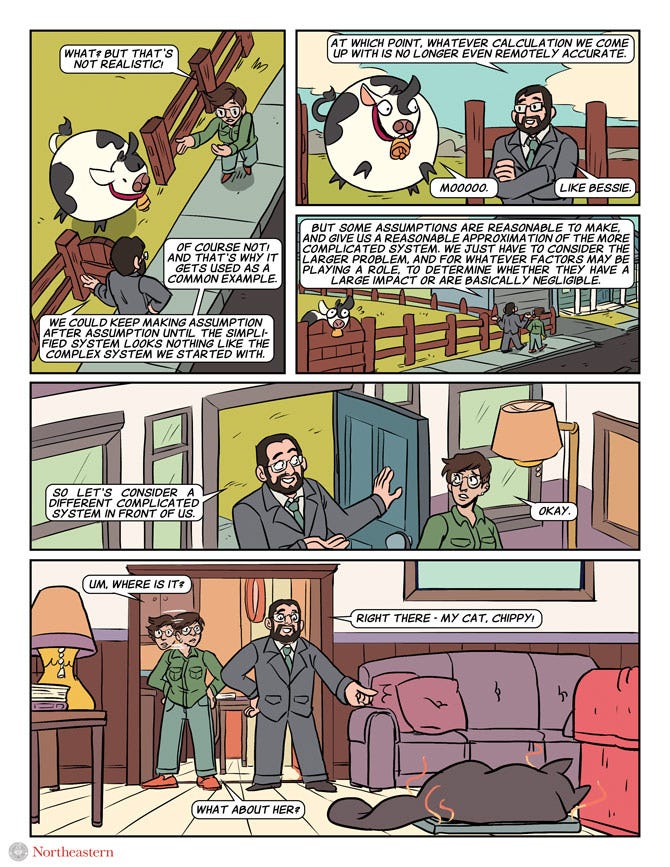

Even if we’re not analysts or statisticians, assumptions vastly shape our world. Having the ability to understand on which ground a decision was made makes us better thinkers. I leave you with this humorous comic from Northeastern University:

That’s exactly how the world is, like a cow that is hard to model. Simplifying how we think about it makes it easier to digest. Yet what if we miss out on something important?

Read the rest of the comic here.

——————————————

Growing Meta is a weekly letter tackling real-world topics from meta angles, such as complexity, analysis or the future. I dedicate time in my weekends to read and share point-of-views that are relevant to how our world is shaped. I also share some of my thoughts on Twitter @NajlaAlariefy.

Have a great weekend!

Najla

References

[1] Birch, Kean. "Techno-economic assumptions." (2017): 433-444.

[2] Joyner, Michael J., and Nigel Paneth. "Seven questions for personalized medicine." Jama 314.10 (2015): 999-1000.

[3] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/precision-medicine-market-revenue-worth-738-8-billion-by-2030-ps-intelligence-301256580.html